@manton Is there a reason the iOS app has to crop images? Sometimes cropping destroys the image. For example, the screenshot in this post was unintelligible when posted through the iOS app. Had to post to my site manually. https://dazeend.org/2018/04/1660/

Posted on April 12, 2018

Read More

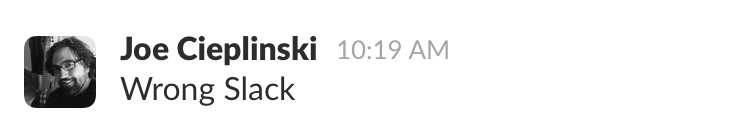

The story of my life.

Posted on April 12, 2018

Read More

I’m just baffled by the idea that the IRS would explicitly permit a client to print, sign, re-scan and upload a form; but literally requires a credit check if the client wants to e-sign the same form. It’s completely nuts.

Posted on April 11, 2018

Read More

Just realized that this week marks episode 256 of Release Notes. It’s hard to believe we’ve published 2^8 of these things without missing a week.

Posted on April 11, 2018

Read More

The IRS regulations surrounding e-signatures are laughable. It’s layer upon layer of security theater.

Posted on April 10, 2018

Read More

Looks look like @Linode will soon be patching their servers for Spectre. I’ve been getting emails with reboot maintenance windows for all my servers.

Posted on April 10, 2018

Read More

More “anniversary” loot!

Posted on April 10, 2018

Read More

Pro tip: When you visit a resort and tell them that you’re celebrating your anniversary, they do all kinds of fun stuff for you.

Pro tip 2: You can celebrate your anniversary anytime you want! Even in April when you were married in October.

(Yes, that’s a towel elephant!)

Posted on April 10, 2018

Read More

Full Archive

Select Month

November 2025 (1)

October 2025 (30)

September 2025 (12)

August 2025 (1)

May 2025 (6)

April 2025 (1)

March 2025 (3)

February 2025 (2)

January 2025 (2)

October 2024 (4)

September 2024 (1)

July 2024 (23)

June 2024 (3)

May 2024 (6)

April 2024 (35)

March 2024 (3)

February 2024 (1)

January 2024 (1)

December 2023 (8)

November 2023 (5)

October 2023 (2)

September 2023 (38)

August 2023 (6)

July 2023 (3)

June 2023 (10)

April 2023 (39)

March 2023 (4)

February 2023 (2)

January 2023 (4)

November 2022 (24)

October 2022 (8)

September 2022 (36)

July 2022 (7)

June 2022 (11)

May 2022 (13)

April 2022 (13)

January 2022 (1)

December 2021 (3)

November 2021 (3)

October 2021 (47)

September 2021 (2)

August 2021 (5)

June 2021 (2)

April 2021 (4)

March 2021 (7)

February 2021 (2)

January 2021 (6)

December 2020 (8)

November 2020 (14)

October 2020 (12)

September 2020 (1)

August 2020 (7)

July 2020 (7)

June 2020 (13)

May 2020 (11)

April 2020 (32)

March 2020 (14)

February 2020 (21)

January 2020 (5)

December 2019 (8)

November 2019 (30)

October 2019 (17)

September 2019 (31)

August 2019 (24)

July 2019 (14)

June 2019 (10)

May 2019 (35)

April 2019 (20)

March 2019 (13)

February 2019 (8)

January 2019 (1)

December 2018 (6)

November 2018 (19)

October 2018 (56)

September 2018 (21)

August 2018 (28)

July 2018 (12)

June 2018 (31)

May 2018 (19)

April 2018 (32)

June 2017 (1)

May 2017 (1)

March 2017 (2)

January 2017 (1)

May 2016 (1)

April 2016 (1)

March 2016 (2)

February 2016 (14)

January 2016 (1)

November 2015 (1)

October 2015 (1)

July 2015 (2)

June 2015 (2)

March 2015 (1)

January 2015 (2)

December 2014 (1)

June 2014 (5)

November 2013 (2)

October 2013 (1)

August 2013 (1)

June 2013 (2)

November 2012 (1)

October 2012 (1)

September 2012 (2)

September 2010 (1)

July 2010 (1)

February 2010 (1)

January 2010 (1)